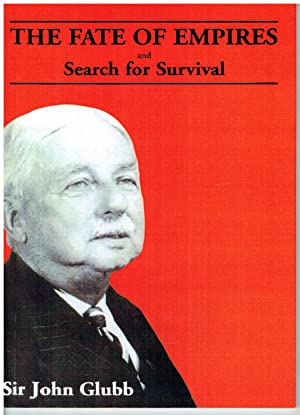

In 1976 Lieutenant General Sir John Glubb published an essay called “The Fate of Empires”. In it Glubb suggests at least two ideas that are influential today. The first is that all empires have a lifespan of 250 years, which corresponds to about 10 human generations. The second is that empires have six stages.

The lifespan of empires seems to be unaffected by its location or the available technology, which suggests that there is an intrinsic human cause. Glubb calls the six stages of empire:

Age of Pioneers

Age of Conquests

Age of Commerce

Age of Affluence

Age of Intellect

Age of Decadence

The six Ages have specific characteristics. The first few Ages seem to include an adventurous and explorative spirit. During the second Age of Conquests, Glubb says that the “initiative of the original conquerors is maintained – in geographical exploration, for example: pioneering new countries, penetrating new forests, climbing unexplored mountains and sailing uncharted seas.” The third Age of Commerce, “[perpetuates] to some degree the adventurous courage of the Age of Conquests”, as people search for new forms of wealth in “far corners of the earth”.

This adventurous spirit is lost with the Age of Affluence. There is a gradual “decline in courage, enterprise and sense of duty”, with money replacing honour and adventure as the “objective of the best young men”. This loss of adventure is compounded in the Age of Intellect where ambition of the young, “once engaged in the pursuit of adventure and military glory, and then in the desire for the accumulation of wealth, now turns to the acquisition of academic honours”.

Glubb was born in 1897, the son of a British army officer. He spent part of his childhood and schooling in Mauritius and Switzerland, served throughout the First World War, then spent decades in the Middle East, including 17 years commanding the Jordan Arab Legion (effectively the Jordanian army). He was a prolific writer on the Middle East and an Arab scholar. Glubb’s ideas might be coloured by his age (79) when it was published, and by his specific life experience spent in the service of a declining empire.

Initial reactions to the essay included accusations of fatalism. But Glubb was clear that his position was completely the opposite – “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves that we are underlings”. He observed that the Age of Decadence isn’t physical: European and American explorers brought up in comfort matched the endurance of locals when travelling in inhospitable places; people who emigrate from a decadent society quickly adopt the energy of their new home.

The essay is enduringly popular, partly because of the outstandingly clear prose, but also because of the ideas. Glubb categorises the Roman Empire and Republic as two separate empires – perhaps there are parallels with the more recent British and American empires. Certainly, the Fate of Empires is often cited with anxiety by people concerned about the possible collapse of American power.